|

| Magazine advertisement, McClure's Magazine, 1900 |

On July 10th, 1909, the Great Northern Railway

began electrified operations in the Cascade Mountains of Washington state. But

before the electric motors went into service, the GN had to get their trains

over the Cascades via a series of switchbacks. This was a terrible waste of

time and effort (but at the time, it was unavoidable). In 1900, the GN opened a tunnel of about 2.5 miles in length.

This tunnel eliminated the switchbacks. However, the combination of heat and smoke emitted by

steam trains operating through this first Cascade Tunnel was so overwhelming

that engine crews and even passengers were overcome. So in 1909, an

electricity-producing power plant was built on the Wenatchee River not far from

Leavenworth, and a section of the line about 4 miles long was electrified

through the first Cascade Tunnel.

|

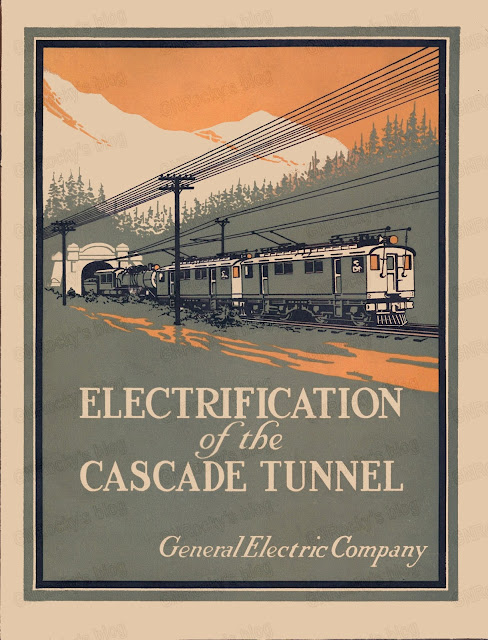

| Cover of GE Bulletin No. 4755, dated June, 1910 |

Here are a few images and historic descriptions of this

electrification effort.

On August 27, 1909, a trade publication called Railway World

published the following explanation of the GN’s strategy to electrify the

4-mile section of their operations over the Cascade Mountains:

This tunnel has

always been a nightmare to passengers and to trainmen. It required an hour

after each train passed to clear it of smoke sufficiently to pass the next, and

its capacity was thus limited to twenty-four a day. To remedy this, a river

beside which the railway runs has been dammed twenty-four miles from the tunnel

and harnessed to an electric generator. Four electric locomotives are in

service and trains can now be sent through – with comfort to the passengers –

as often as the speed regulations will permit.

On November 14, 1908, the Railway and Engineering Review

published this article about the GN electrification project:

The General Electric Co. has

completed several electric locomotives for the Great Northern Ry. on its order

for rolling equipment for the Cascade Tunnel section of the road. This part of

the line is now in process of electrification and the electric locomotives will

be used for hauling both freight and passenger trains through the tunnel and

over the heavy grades adjacent. The length of this tunnel—about 2 3/8

miles—together with the fact that it is unequipped with ventilating shafts of

any description, has rendered the employment of some motive power other than

the steam locomotive almost a necessity. In addition to the danger arising from

the gases emitted by steam locomotives, and the possible obscuring of signal light

by smoke, the accumulation of sooty matter has given rise to a slipperiness of

the rails that materially increases the difficulties of the grade, which,

throughout the tunnel, is 1.7 per cent.

To meet the requirements of the

traffic, four of the electric locomotives have been ordered. Each of these

units will have a weight of approximately 113 tons, this weight being entirely

on the drivers, and will be equipped with four 400-h.p. three-phase induction

motors mounted on two articulated bogie trucks. The locomotive units are

designed to be operated by the Sprague-General Electric multiple unit control,

so that three or four may be operated from one controller on any unit.

In normal operation, two of these

units will haul a train having a gross weight of from 1200 to 1500 tons up a

grade varying from 1.6 to 2.2 per cent at a speed of 15 miles per hour. The

motors will be wound for 500 volts per phase, and will be fed from two

step-down transformers located on the car. They will be controlled by resistance

steps in the secondary or armature circuit.

On down grade the motors will

tend to control the train by regeneration, and at any speed in excess of 15

miles per hour, will return energy to the line, thus tending to assist other

trains that may be ascending the grade at the time. If, at the moment, there is

no such train to utilize this returned energy, it will be dissipated by water

rheostats at the power house. An additional advantage in thus using the

regenerative feature of the motors on a descending grade is, of course, the

braking effect and the consequent saving of brake shoes and tires.

Electric power will be supplied

from a hydraulic plant located on the Wenatchee River, and distant about

thirty miles from the tunnel. The generating equipment will consist of two

2000-kw., 25-cycle, three-phase generators, which will be driven by water

power. From the station the power will be transmitted at 30,000 volts by means

of duplicate transmission lines, and will be stepped down by transformers at

the mouth of the tunnel to 6600 volts. The locomotives will take the current

from an overhead wire, which will be of a modified catenary type, utilizing the

new fish tail strain insulator of the General Electric Co. The voltage on the

trolley wire will be 6600, and this pressure, as indicated above, will be

stepped down before entering the motors by transformers on the locomotive to a maximum

of 500 volts per phase.

The locomotives placed in service on the newly electrified

section were numbered 5000, 5001, 5002, and 5003. According to the seminal work by Ken Middleton

and Norm Keyes on GN locomotives, published in 1980 in RLHS Bulletin #143, these four

electric motors were delivered to the GN by General Electric in February and

March of 1909. The motors remained in service until they were replaced by new

locomotives in the mid to late 1920s, in preparation for the extension of

electric operations all the way from Wenatchee to Skykomish.

On November 12, 1909, a meeting of the American Institute of

Electrical Engineers was held in New York City. The keynote speaker of the

event was Dr. Cary T. Hutchinson of the Great Northern Railway. Dr. Hutchinson

provided the essence of a paper he wrote titled “The Electric System of the

Great Northern Railway Company at Cascade Tunnel.” Part of his abbreviated

material was published in an issue of the Electrical Review and Western

Electrician. Here are some

comments Dr. Hutchinson made regarding the first operations of the electrified

section in the Cascades:

The electric service was started

on July 10 last, although one or two trains had been handled previously. From

that time to August 11 practically the entire east-bound service of the company

had been handled by electric locomotives. During this period there were 212

train movements, of which eighty-two were freight, ninety-eight passenger and thirty-two

special. In each case, the steam locomotive was hauled through with the train.

The total tonnage hauled was 275,000 tons.

Dr. Hutchinson concluded his remarks by enumerating several

distinct advantages of electrified locomotion in this instance:

1.

Maximum electrical and mechanical simplicity

This point is of great importance and was one of a number of reasons for using the three-phase system. The motors will stand any amount of abuse and rough use.

This point is of great importance and was one of a number of reasons for using the three-phase system. The motors will stand any amount of abuse and rough use.

2.

Greater continuous output within a given

space than can be obtained from any other form of motor This is shown by

comparison with other electric locomotives, which is due to the fact that the

losses can be kept lower in the three-phase motor than in any other type.

3.

Uniform torque

This is important, particularly at starting. The three-phase motor will work to a three or four per cent greater coefficience of adhesion than a single-phase motor of fifteen cycles.

This is important, particularly at starting. The three-phase motor will work to a three or four per cent greater coefficience of adhesion than a single-phase motor of fifteen cycles.

4.

The possibility of using twenty-five cycles

This is important, as it leads to a less cost and a better transformation of power-station apparatus; moreover, it is standard and the power supply can readily be used for other purposes as well as for traction; a commercial supply can be provided.

This is important, as it leads to a less cost and a better transformation of power-station apparatus; moreover, it is standard and the power supply can readily be used for other purposes as well as for traction; a commercial supply can be provided.

5.

Constant speed

This is ordinarily stated as a disadvantage of the three-phase motor. But it is a distinct advantage in mountain service, particularly the limitation of the speed on down grades. It has also an advantage on up-grades: meeting points can be arranged with greater definiteness.

This is ordinarily stated as a disadvantage of the three-phase motor. But it is a distinct advantage in mountain service, particularly the limitation of the speed on down grades. It has also an advantage on up-grades: meeting points can be arranged with greater definiteness.

6.

Regeneration on downgrades

This matter has been discussed since the earliest days of electric traction, but has not been, up to the present time, put into practice. Although this result can be attained with other forms or motors, yet it is most perfectly attained by three-phase motors. There being no complications involved. This is of importance in reducing the power-house capacity required for a given space. Although no doubt the saving in power-house capacity will not be as great as indicated by theory, owing to the various emergencies that must be provided for; nevertheless, there will be a material saving.

This matter has been discussed since the earliest days of electric traction, but has not been, up to the present time, put into practice. Although this result can be attained with other forms or motors, yet it is most perfectly attained by three-phase motors. There being no complications involved. This is of importance in reducing the power-house capacity required for a given space. Although no doubt the saving in power-house capacity will not be as great as indicated by theory, owing to the various emergencies that must be provided for; nevertheless, there will be a material saving.

7.

Excessive short-circuit current is

impossible, and consequently destructive torque on the gears and driving

rigging is eliminated

There will be no necessity for the complication of the friction connection between the armature and driving wheels, as in the recent large direct-current locomotives.

There will be no necessity for the complication of the friction connection between the armature and driving wheels, as in the recent large direct-current locomotives.

8.

Impossibility of excessive speed

Even when the wheel slips the speed remains constant. Therefore, the maximum stresses put on the motor are less and are more accurately known than with any other form of motor.

Even when the wheel slips the speed remains constant. Therefore, the maximum stresses put on the motor are less and are more accurately known than with any other form of motor.

To be even-handed about the thing, Dr. Hutchinson then

enumerated six issues he framed as “the principal disadvantages of three-phase

motors for traction use” that were commonly stated to be the following

(although he also countered several of those points as they applied to the GN

operations):

1.

The constant speed

This is rather an advantage for this class of service.

This is rather an advantage for this class of service.

2.

Constant power

The fact is that the motor is a constant power motor, and therefore requires the same power at starting and accelerating as at full speed.

The fact is that the motor is a constant power motor, and therefore requires the same power at starting and accelerating as at full speed.

3.

Small mechanical clearance

In this particular motor the clearance is one-eighth of an inch, which is ample for all practical purposes.

In this particular motor the clearance is one-eighth of an inch, which is ample for all practical purposes.

4.

Inequality of load on several motors of a locomotive

due to differences in diameter of driving wheels

To meet this, an adjustable resistance is included in the rotor of each motor. The motors are then balanced up and no further attention is required as long as the wear on the driving wheels is approximately the same.

To meet this, an adjustable resistance is included in the rotor of each motor. The motors are then balanced up and no further attention is required as long as the wear on the driving wheels is approximately the same.

5.

Low-power factor of the system

This does not seem to be borne out by practice. The power factor, as shown by the switchboard instruments in the power house, is eighty-five per cent.

This does not seem to be borne out by practice. The power factor, as shown by the switchboard instruments in the power house, is eighty-five per cent.

6.

Two overhead wires

There is no doubt that two wires will cause more trouble than one, and in case of complicated yard structure, it might not be practicable to use two overhead wires.

There is no doubt that two wires will cause more trouble than one, and in case of complicated yard structure, it might not be practicable to use two overhead wires.

One of the attendees of the banquet in New York was J. H.

Davis, electrical engineer with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Davis marveled

at the success of the Great Northern Railway in conquering their motive power

issues through the Cascade Tunnel, saying: “It is the first attempt in this

country to use the three-phase induction motor for handling heavy passenger and

freight trains on a trunk line railroad.”

Dr. Hutchinson practically made a second career for himself

on the speaking circuit, trotting the fruits of his work in the Cascades to

countless groups of professional electrical engineers. One of those sessions

was held in Pullman, Washington, with a group gathered at the State College of

Washington (later to be named Washington State University – my alma mater,

coincidentally). Some in attendance had worked on the tunnel the previous

summer.

Less than a year after the GN instituted electrified motive

power through the Cascade Tunnel section, a massive avalanche swept down

through the little railroad village of Wellington (later renamed Tye). This

disaster has generated a great deal of research and reporting. Even the

community of electrical engineers had their angle on the tragic events:

It may not be generally known

that the avalanche which occurred at Wellington, at the western end of the

tunnel, on March 1, caused considerable damage to the equipment of the system.

All four of the electric locomotives, with two trains, three steam locomotives,

and a rotary snow-plow, were swept away by the slide. Some idea of its force

may be gained from the fact that the weight of each of the electric locomotives

is 230,000 lb. A portion of the overhead catenary construction was also swept

away. The extent of the damage to the electric locomotives has not yet been

determined. If much of the apparatus has to be rewound, it may be six months before

the electric service can be resumed, as the locomotives will probably have to

be sent to Seattle or some other city for repair.

I don’t know anything about the efforts that took place

putting the line, and the electrification system, back in service after the

avalanche, but suffice it to say the repairs were eventually

accomplished. Jumping ahead several years, a new fleet of electric motors was

purchased to operate over the dramatically lengthened section of electrified

railroad between Wenatchee and Skykomish. The four original electric motors

were retired in May of 1927 as they were replaced with the new Z-1 and Y-1

electrics from about 1926 to 1928, just prior to completion of the new 8-mile

Cascade Tunnel.

From a November 14, 1925, article published in Railway Age,

here is an explanation of how the electric motors were operated in conjunction

with steam engines, and the typical times involved with running this motive

power mix over the Cascade Mountains:

A 2,500-ton time freight, out of

Seattle, or rather Interbay, the terminal yard, consisting of about 60 cars,

covers the 80 miles to Skykomish in approximately 5½ hours when hauled by a

250-ton Mikado type 2-8-2 oil burning locomotive having a normal tractive power

of 64,300 lb. At Skykomish, two 2-6 + 8-0 mallet type locomotives of 260 tons

and developing a tractive effort of 78,300 lb., are cut into the train at about

uniform distance apart, to assist on the 2.2 percent grade to Tye. Including a

delay at Skykomish for this operation of one hour and for water at Scenic of 20

minutes, the 21.4 miles to Tye is covered in 4½ hours. On arrival at Tye, the steam

helpers are replaced in 30 minutes by the electric locomotives located two

ahead and two in the center of the train, and from Tye, the run to Cascade

tunnel station is made in 22 minutes. Allowing 15 minutes at Cascade tunnel for

cutting out the electrics and inspecting air brakes, the train when reassembled

completes the remaining 53 miles to Wenatchee in four hours.

Additional sources

of information about Great Northern Railway electrification:

Web site devoted

to Milwaukee Road electrification – has a ton of great GN material too

·

GNRHS

Reference Sheet #18 (April 1976), Great

Northern Three-phase Electric Locomotive by William McGinley, Michael

Oltman, James Vyverberg, Kenneth Middleton, and Charles Wood

·

GNRHS

Reference Sheet #58 (September 1983), Great

Northern Modernized Class Y-1 Electrics by Stan Townsend

·

GNRHS

Reference Sheet #210 (December 1993), Z-1

Class Electric Locomotives by Fr. Dale Peterka

·

GNRHS

Reference Sheet #316 (September 2003), Great

Northern Railway Electrification by Stan Townsend